Long-term care residents deserve better

Staff at continuing care facilities aren’t the problem

The first waged job I ever had was at the Craiglee Nursing Home in Scarborough, Ontario. It was around the corner from my home and the pay was $11.36 an hour. This was a great score for a 14-year-old me, given that the minimum wage then was $2.65 per hour, $2.15 if you were under 18.

I lasted four shifts before I quit. The physical space was depressing and dark. The building, privately owned and operated, had been open since 1966 so was exempt from the laws imposed by the 1972 Nursing Homes Act. There was not enough time to engage with the residents who so clearly needed it. The work was too hard; I was completely out of my depth and had received little training. I went to work at Burger King for $2.15 an hour.

My grandmother moved into that nursing home a few years after that. It was convenient for my mother to visit frequently and ensure she got the care she needed. This was a huge concern at the time; the poor quality of care in nursing homes for seniors, the disabled, and those with mental health issues was frequently in the headlines and those headlines often contained words like ‘abuse’ and ‘neglect’.

I take you on this little trip down memory lane for a few reasons. First, to illustrate that four decades ago, workers in long-term care facilities were paid relatively well. Office clerks with a high school education earned about four dollars an hour; my cousins and aunt working on the General Motors assembly line and members of the autoworkers’ union made seven. That changed. Why are workers in these facilities today paid so little that they are forced to work two or three different jobs just to feed their families?

Second, problems with continuing care in this country have been going on for almost my entire life. While COVID-19 and the disproportionate number of deaths in seniors homes these past weeks have turned our attention to the problems in our continuing care system, many have been raising the alarms about these problems for decades. That hasn’t changed. And, again, we need to ask ourselves why.

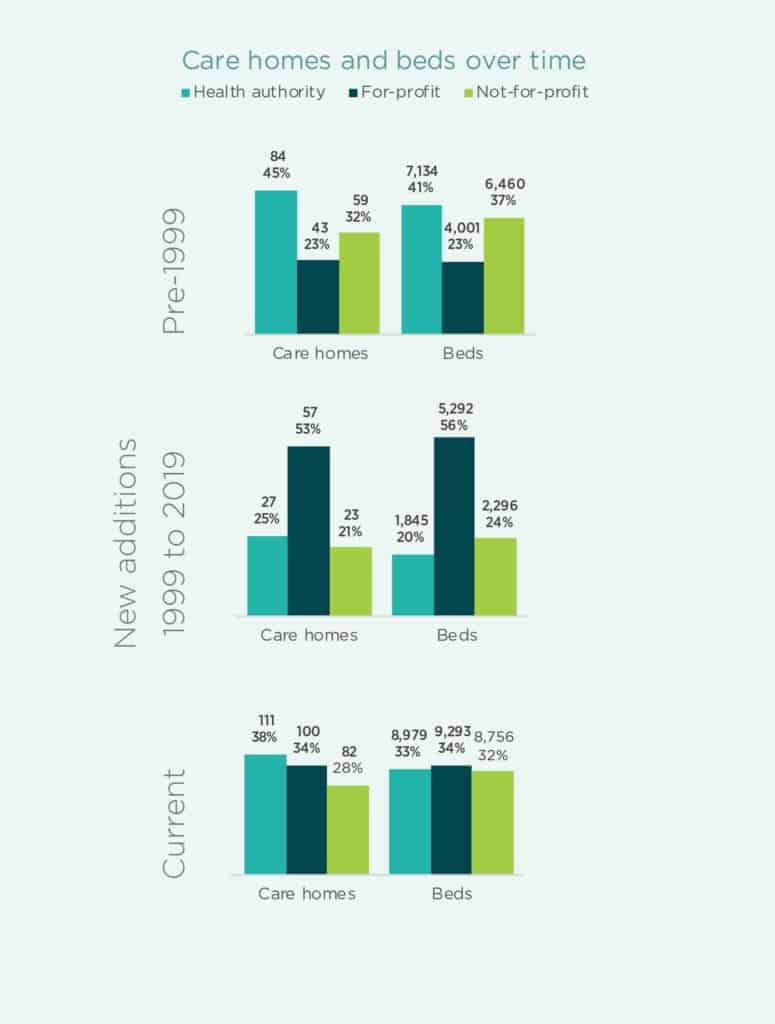

Long-term care in our country is offered through a mix of public, private for-profit, private not-for-profit, and religious-based providers. Since the 1990s, the shift away from public provision of care for our most vulnerable to for-profit has been profound.

Not long after British Columbia reported its first confirmed case of COVID-19 on Jan. 28, the province’s Seniors Advocate tabled ‘A Billion Reasons to Care’, a report on the first review of the $1.4 billion-dollar contracted long-term care sector in the province.

That report found that 33 per cent of publicly funded long-term-care beds in B.C. are operated directly by public health authorities. The remainder are operated by for-profit companies (35 per cent) and not-for-profit societies (32 per cent) on contract with one of the five regional health authorities. This report showed how much for-profit operations divert the money going to direct care. And, it showed the incursion of for-profit provision of long-term care since the 1990s.

According to the report, “For-profit care homes, by the nature of their business, expect to demonstrate a profit/surplus; this underlying fact sets in motion incentives that may, at times, conflict with the best interests of the resident.”

These findings echo a 2016 study by the University of Alberta’s Parkland Institute which showed the disproportionate growth of the for-profit long-term care industry in Alberta over six years. This didn’t end when the NDP were elected in our province. This is a multi-partisan failure.

Workers in private for-profit homes are just as dedicated as those in publicly-operated and non-profit facilities. That isn’t the problem. The problem is that their employers aren’t motivated to provide a public good; they’re motivated by profit. And funding formulas delivered by governments are driving non-profit employers to devalue their staff just as much as the for-profits.

In 2018, the Conference Board of Canada forecasted that, by 2035, an additional 199,000 new long-term care beds will be needed to accommodate new demand in this country. We don’t have the luxury of thinking long and hard about how to deal with this. What is clearly lacking is the political will.

Featured Image: