Why treaty is more than a word

Eleven treaties were signed between Indigenous nations and the Canadian government, with the last signed in 1921.

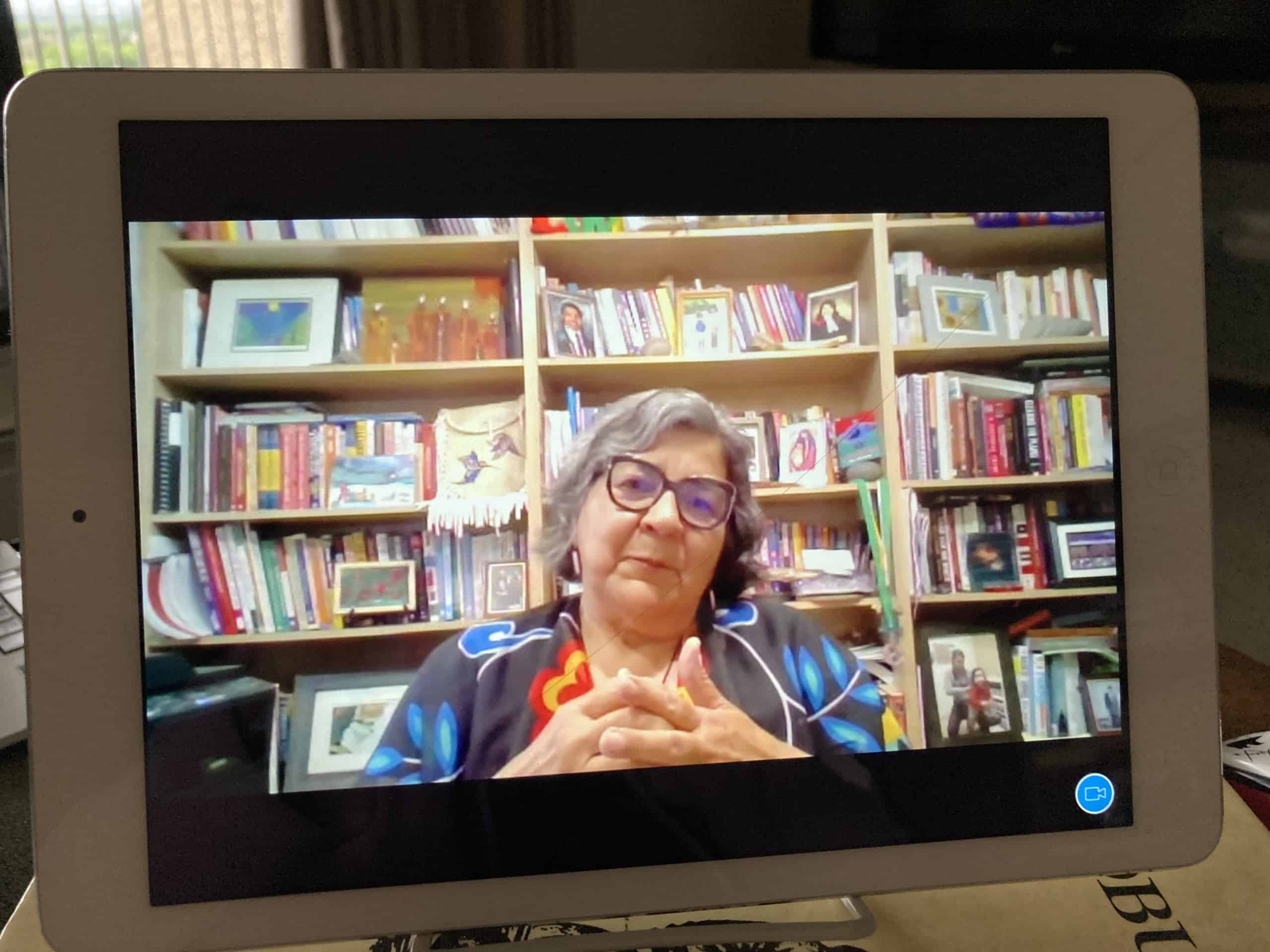

Today, their significance is crucial to our understanding, said Dr. Patricia Makokis of Saddle Lake Cree Nation near St. Paul, Alberta. On June 8 during a Zoom presentation called Treaty Talk & Treaty Walk gathering and panel discussion, Makokis spoke on the topic, along with other Cree and non-Cree speakers.

In 2018, Makokis joined forces with the University of Alberta, City of Edmonton, and others to film the documentary Treaty Talk – Sharing the River of Life. In 2019, Makokis again worked as film producer of a follow-up documentary called Treaty Walk – A Journey for Common Ground, funded by Health Sciences Association of Alberta (HSAA).

Both documentaries help educate about the effect of treaties on both sides.

Dr. Diana Steinhauer, president of Yellowhead University, explained that for Indigenous peoples, the essence of Treaty Six, which includes the Edmonton area, was an unwritten, oral agreement to be allies with the newcomers. For the signers representing the Canadian government, the written word was law, putting control of Indigenous lives and land in their hands.

The documentaries came after a boycott of St. Paul, the nearest town to Saddle Lake Cree Nation. Members of the Nation were angry with the constant racism they faced in St. Paul. The anger started when teenage boys in a black truck shouted degrading insults at Pamela Quinn and her mother, Florence Quinn, teachers from Kihew Asiniy Education Centre, as they exited the movies in St. Paul in 2005. The boycott of St. Paul’s businesses ended one year later after the town formally apologized.

Maureen Miller, St. Paul’s mayor, was shaken by the experience. She spoke in the documentary, explaining many residents were “afraid to acknowledge that their beliefs could be different.” The boycott cost the city millions of dollars.

In the Zoom presentation, Pamela Quinn said, “I want to be able to walk into a place and feel like I’m a human being, to be comfortable enough and safe enough to be who I am and be accepted.”

Treaty Walk follows a group of people from Indigenous and non-Indigenous cultures, trekking from Edmonton to Calgary. Their goal was to learn about truth and reconciliation together. As they walk through blazing heat, thunderstorms, lightning, torrential rain, and even snow, they get to know each other. One trekker honestly shares that when she arrived in Canada more than a decade ago, she was told many negative things about Indigenous people. Walking with them as a member of HSSA, she learned how kind and good they were.

As HSSA speaker Scott Macdougall observed, “Treaties matter. We all benefit from these treaties. We haven’t had a chance to get to know each other.”

Makokis’s grandson, Atayoh Makokis, appears in the films. Only three years old at the time, the happy boy plays outside without a care in the world. Later, he drums and sings the “Grandmother Song” with confidence.

“I want my grandson to grow up without having to face racism,” said Makoksis. “If we are going to change the Canadian narrative, we are going to do it together. The treaties were about friendship and about sharing the land.”

In Treaty Talk, Steve Andreas of Saddle Lake Cree Nation asked, “Are you willing to sit down and share what you believe and respectfully listen to somebody else’s beliefs and then enter into a dialogue? And have a cup of tea?”

After watching the films and hearing from the speakers, the answer should decidedly be, “Yes.”

To watch both documentaries, visit www.treatytalk.com.