Addictions treatment is crucial

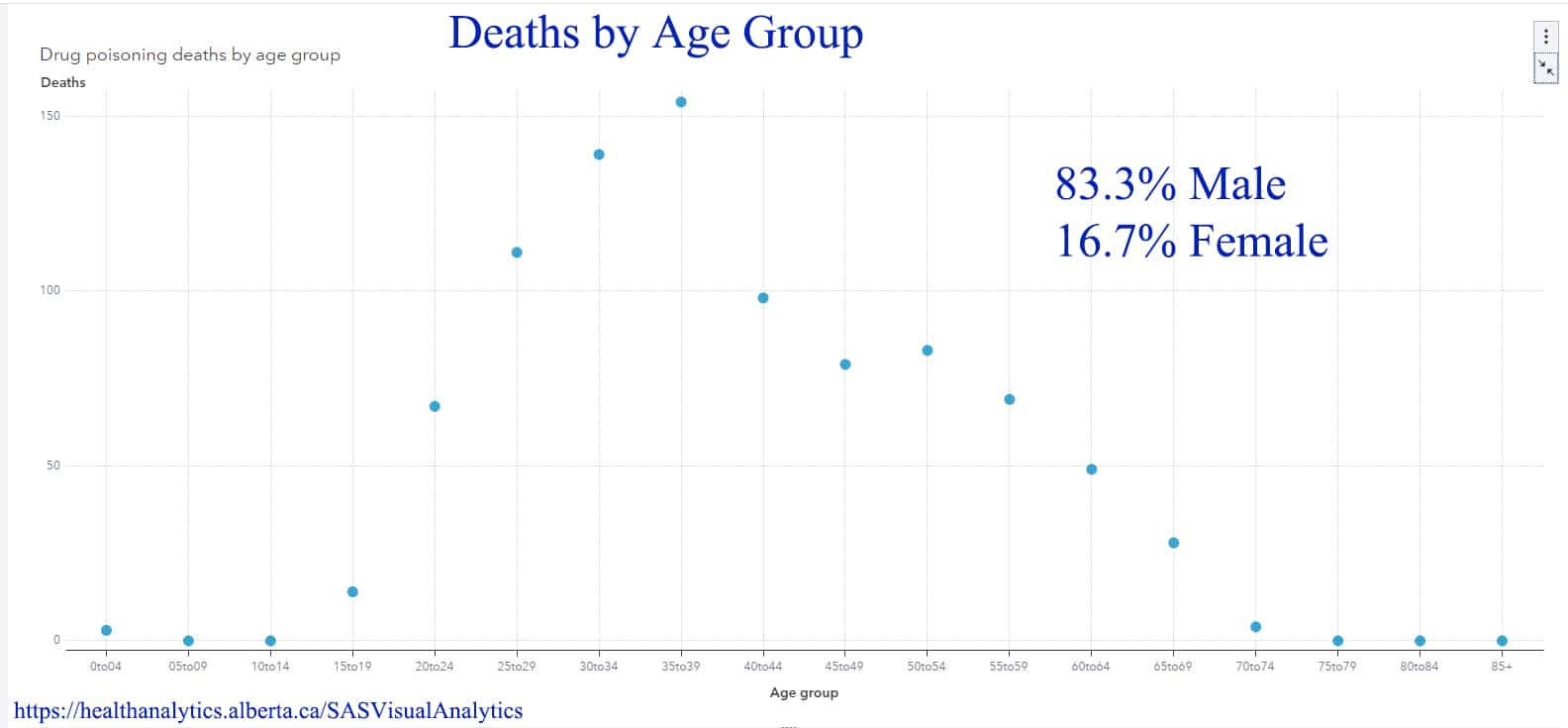

Addictions are present in nearly every age cohort and across the socio-economic divide. While in the inner city we see drug use on the street, addictions are an issue everywhere.

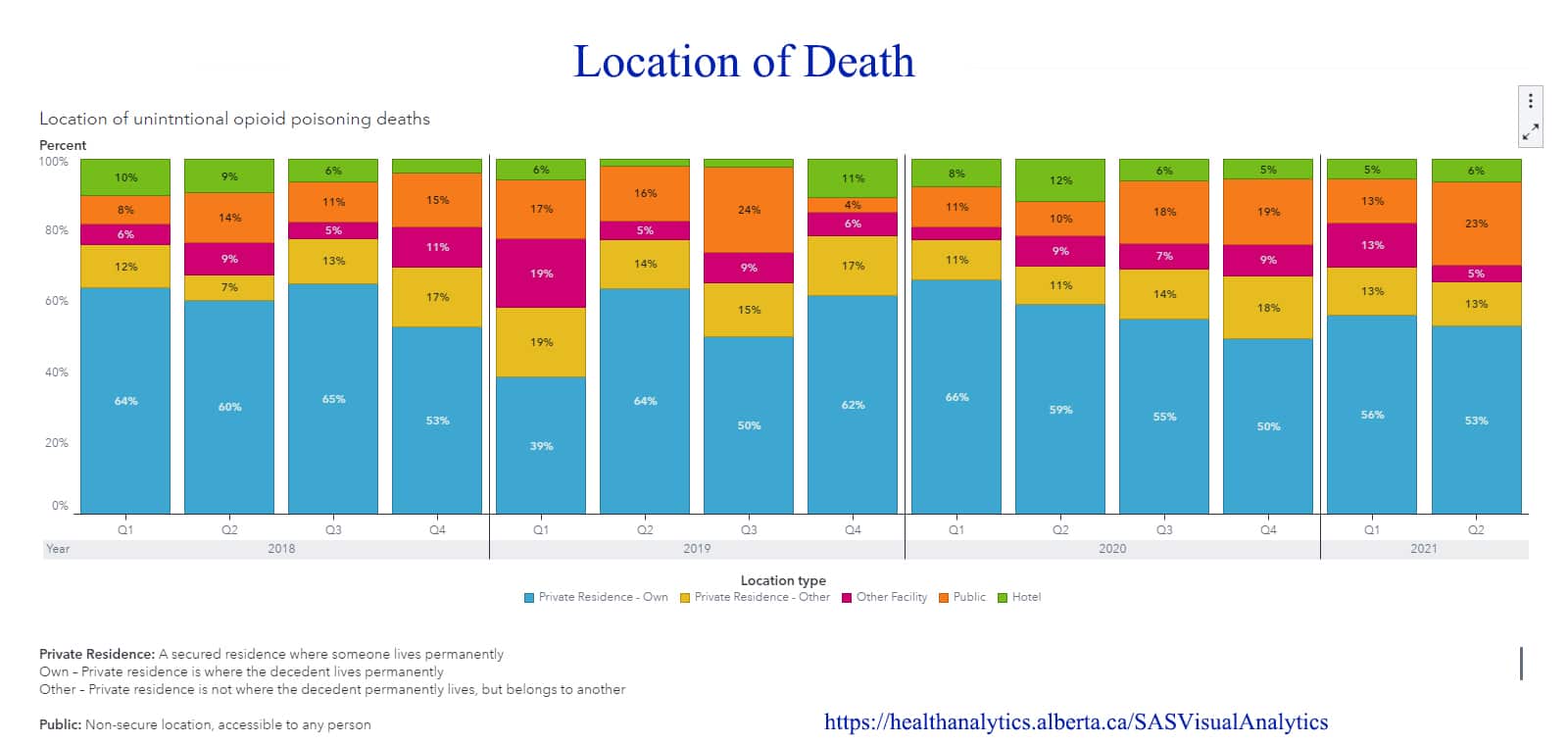

According to the Government of Alberta’s health analytics, most people using drugs die in their own or another person’s home. However, in the past two years, the percentage of people dying on the street increased from 12 to 25 per cent.

The UCP’s addictions strategy is to move away from harm reduction. In 2019, Premier Jason Kenney stated, “Harm reduction efforts certainly have a place within the spectrum of public-health responses to the soaring opioid death rate, but not at the expense of life-saving treatment and recovery.”

According to a CBC article published on July 25, 2020, “Harm reduction is a method that aims to reduce fatality rates and the harm associated with drug use, while acknowledging that abstinence is not always a realistic goal.”

In 2019, $140 million in treatment funding was announced. This includes $25 million of funding for five new treatment centres across the province, some of which were meant to open in early 2021. None of the five facilities have yet opened, or even begun building.

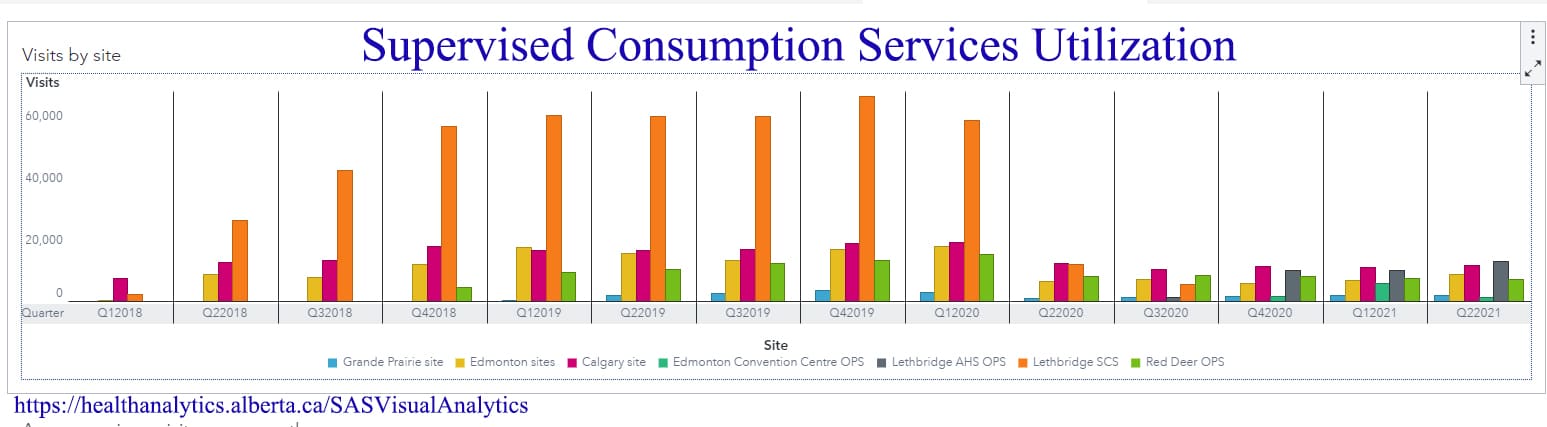

Existing funding for harm reduction has stayed in place but has not increased—despite the increase in drug-related deaths, particularly in the past two years. For 2021, $15.7 million is allocated to five supervised drug-use and three overdose-prevention sites in Alberta. Many facilities have caps on the number of people they can serve with the funding they are provided, which is evident on the streets of our community. The problem is exacerbated by the closure of the Boyle McCauley Safe Consumption site and the decrease in funding. People accessing the services must also present a personal health number, which is a problem because many people in that situation either don’t have one or don’t carry one.

Government funding announcements are confusing. While an overall budget is announced and published, there is little information other than news releases. The announcements sound hopeful, but it’s not clear how many people will actually be helped.

Using Lethbridge as an example, $2 million was cut and the ARCHES safe consumption site closed. The site was closed amid allegations of misuse of funding, yet an investigation revealed that the money was used appropriately and it was just a reporting error. According to data released to Lethbridge News Now, ARCHES had 848 clients for a total of 64,730 uses (averaging 460 per day). The approach was to switch to treatment rather than harm reduction. According to a July 25, 2020 Global News article, “In total, 125 long-term resident addiction treatment beds will be created: 75 on the Blood Tribe and 50 in Lethbridge County. As well, $1 million annually will go toward creating 16 new beds at the Foothills Centre in Fort Macleod, and $1.2 million annually to fund 16 new beds in the City of Lethbridge.”

The government provides no analysis to show how many people will be treated in those beds in a year. Given that average treatment periods are 30-90 days, they may serve 60 to 180 clients per year.

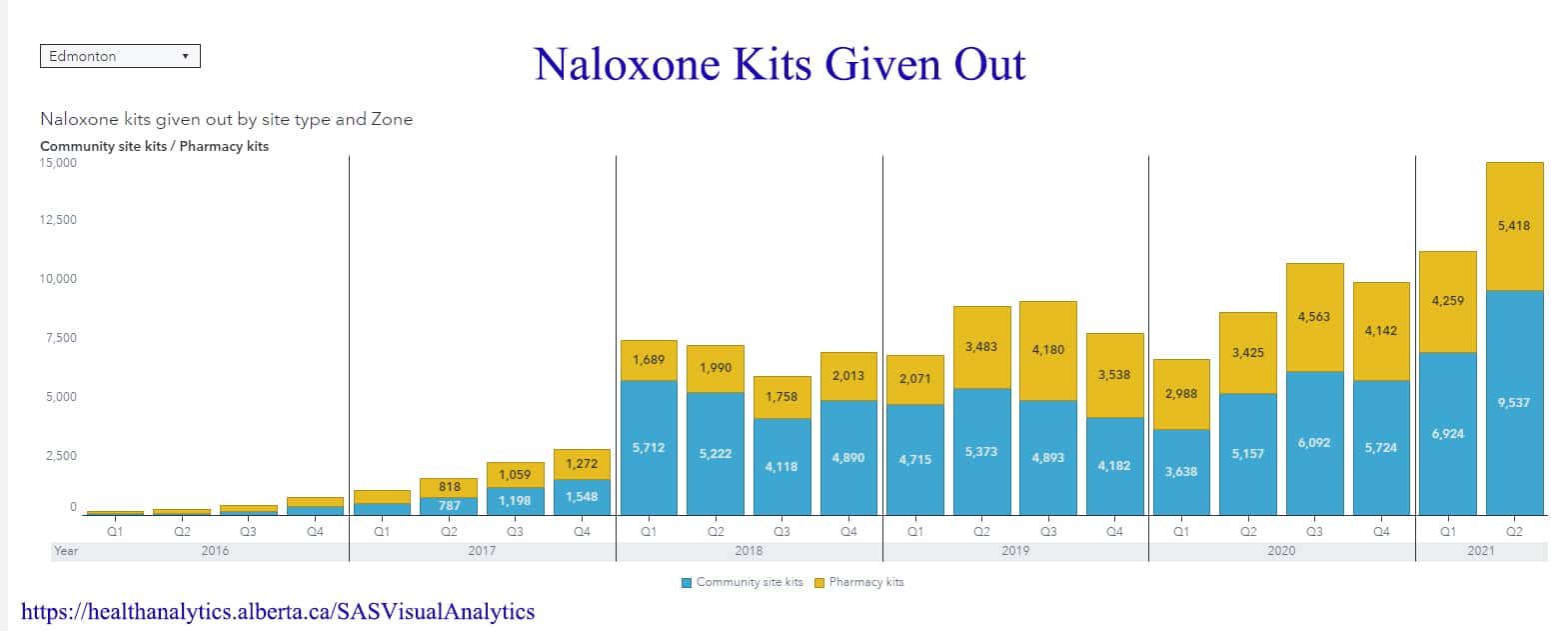

These policies have created a situation by which harm reduction efforts have fallen to the community. Naloxone kits are the best current method we have of dealing with overdoses, and there has been a considerable increase in kits given out over the past two years.

If you or a loved one is facing an addiction, first call 211 for information about available services. The logistics of accessing treatment can be tricky. The first stage requires detox, as most addictions treatment facilities require a period of sobriety before clients can use the services. Residential (live-in) facilities also have waitlists, so timing the detox period with the availability of addictions treatment is a barrier to accessing care. In positive news, publicly-funded residential treatment centres in Alberta are free, even for those without secondary health insurance.

Some treatment sites are Christian, some Indigenous, and some secular. For women who want to complete their treatment while parenting their children (such as single mothers with no family support) there is only one treatment centre, and it is distinctly Christian faith-based. Options that address issues faced by LGBTQ clients are also somewhat limited. Men have more treatment options given their higher rate of addictions, but no access to parenting/treatment facilities.

Providing live-in healthcare facilities for addictions is a laudable goal, but also unrealistic. Not many people can afford to halt their lives for 30 to 90 days to deal with their health issues. The Government of Alberta’s policies create considerable gaps in services. Increased funds for harm reduction would give another option to those who are not ready or able to deal with their addiction with abstinence-based treatments.

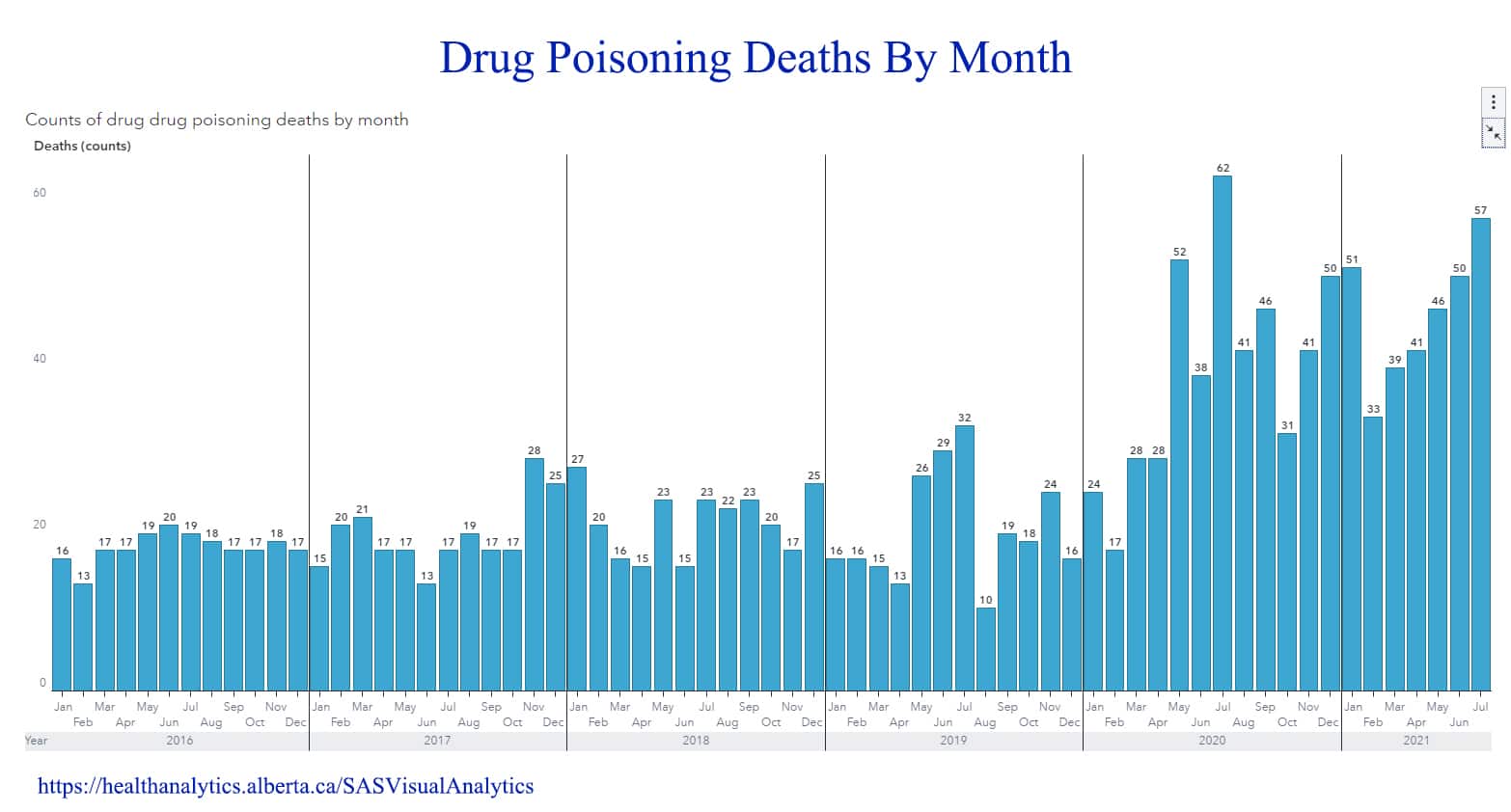

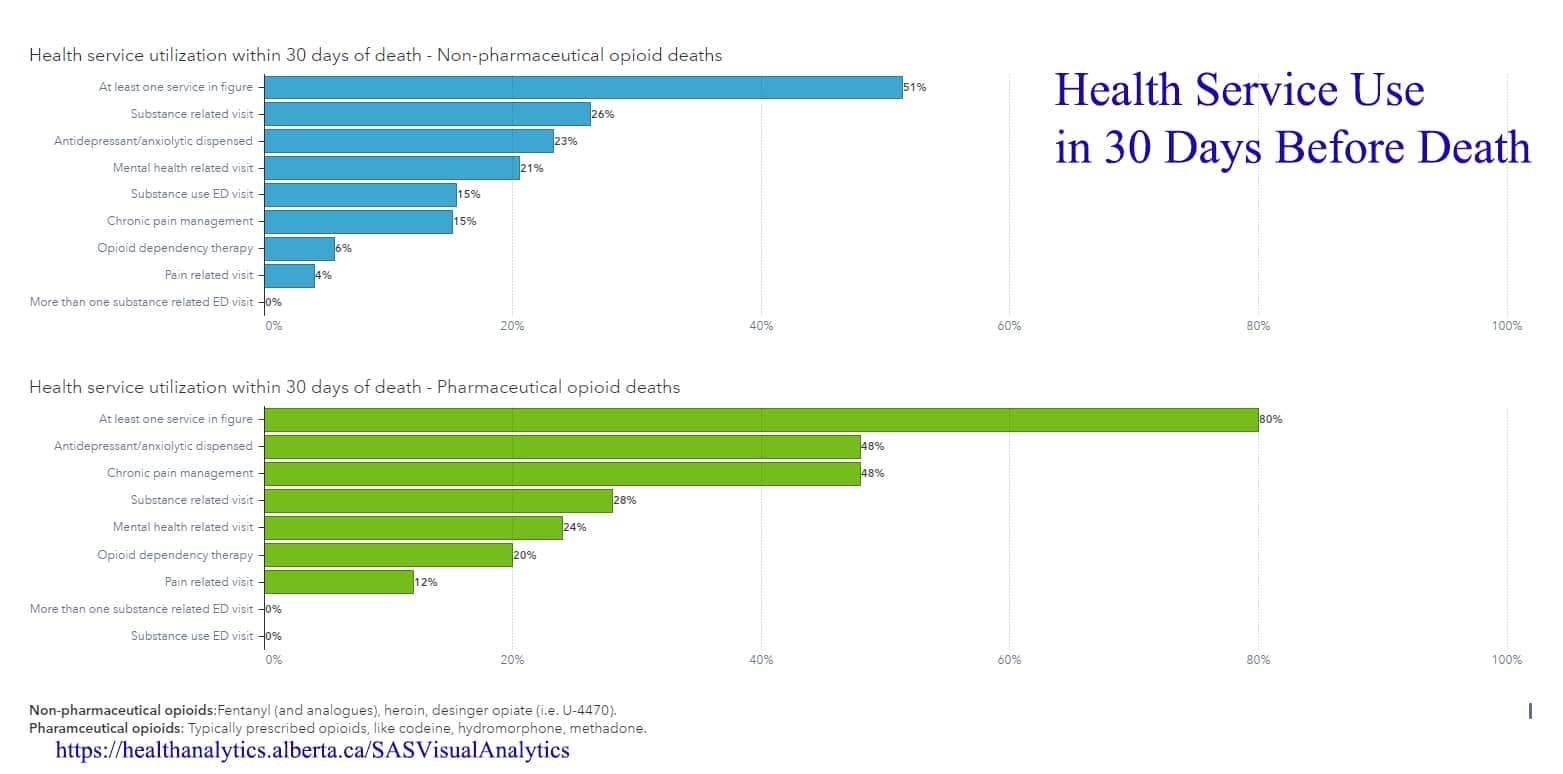

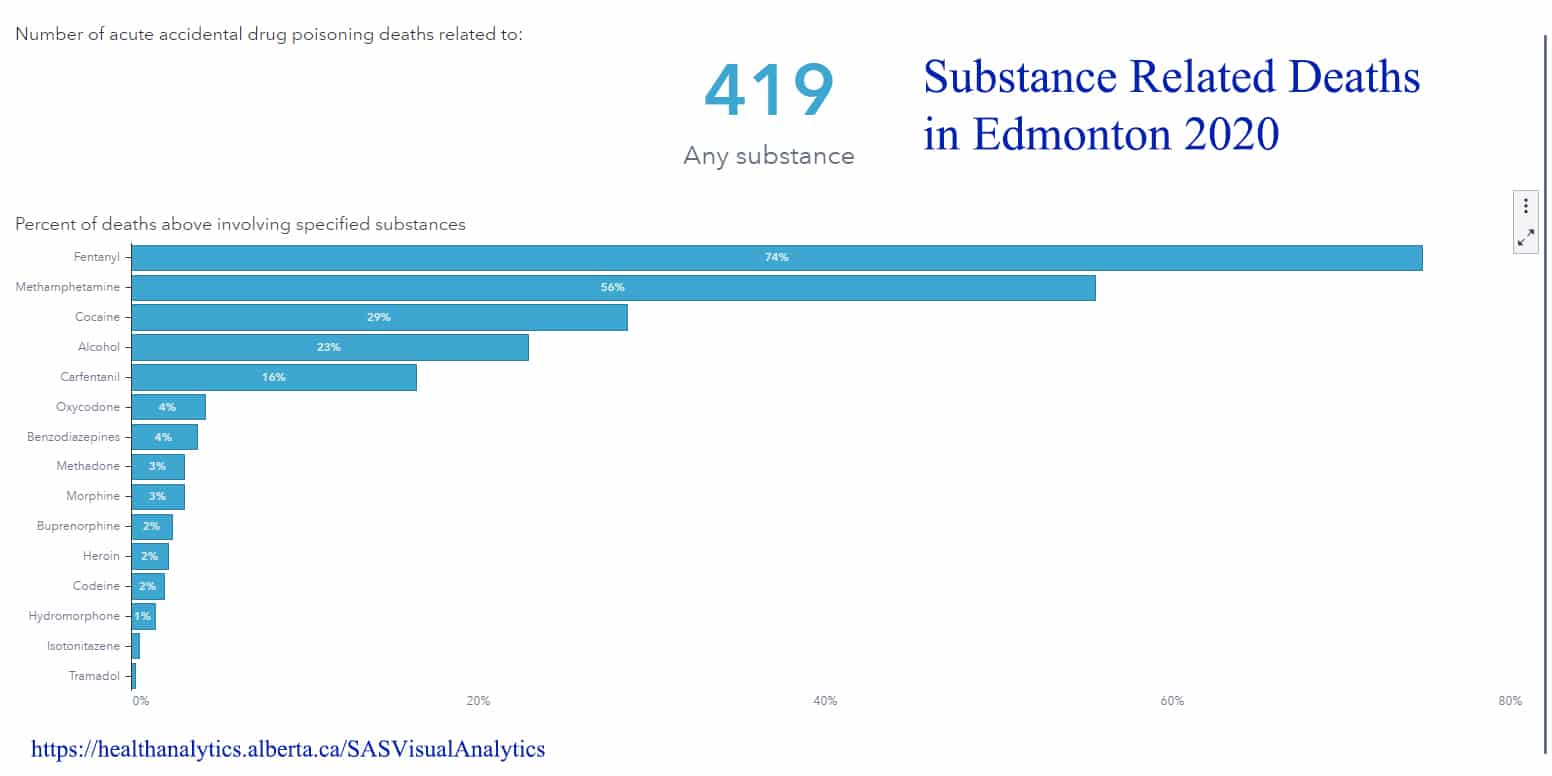

According to health analytics from the Alberta government, addictions and deaths related to addictions span all ages of Albertans and are not limited to street-drug users. Nearly half of the people who died accessed Alberta Health Services for help in the 30 days before their deaths. Most importantly, this problem has increased considerably during COVID-19.

It is clear that people who struggle with addictions are attempting to access health care, but are not being served by the current system.