What makes a resilient garden?

On Aug. 24, gardeners gathered at Alberta Avenue Community League for a garden design workshop, presented by educator, master gardener, and permaculture designer Dustin Bajer of Shrubscriber, in partnership with E4C.

Bajer taught participants permaculture principles and four techniques to create or improve their gardens, emphasizing sustainability and working with nature. According to Bajer, an ecologically designed garden decreases labour, waste, watering, and also increases yield.

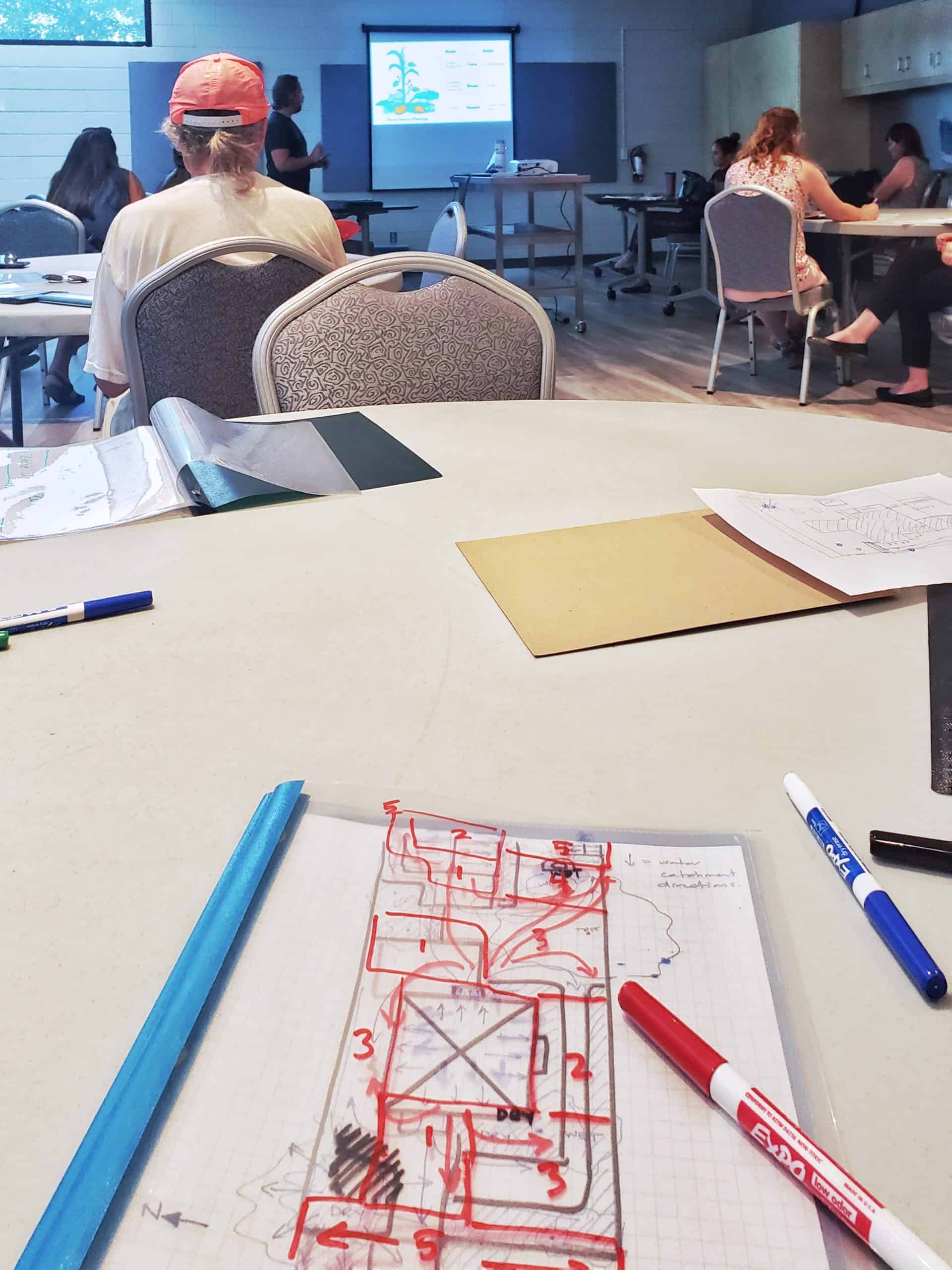

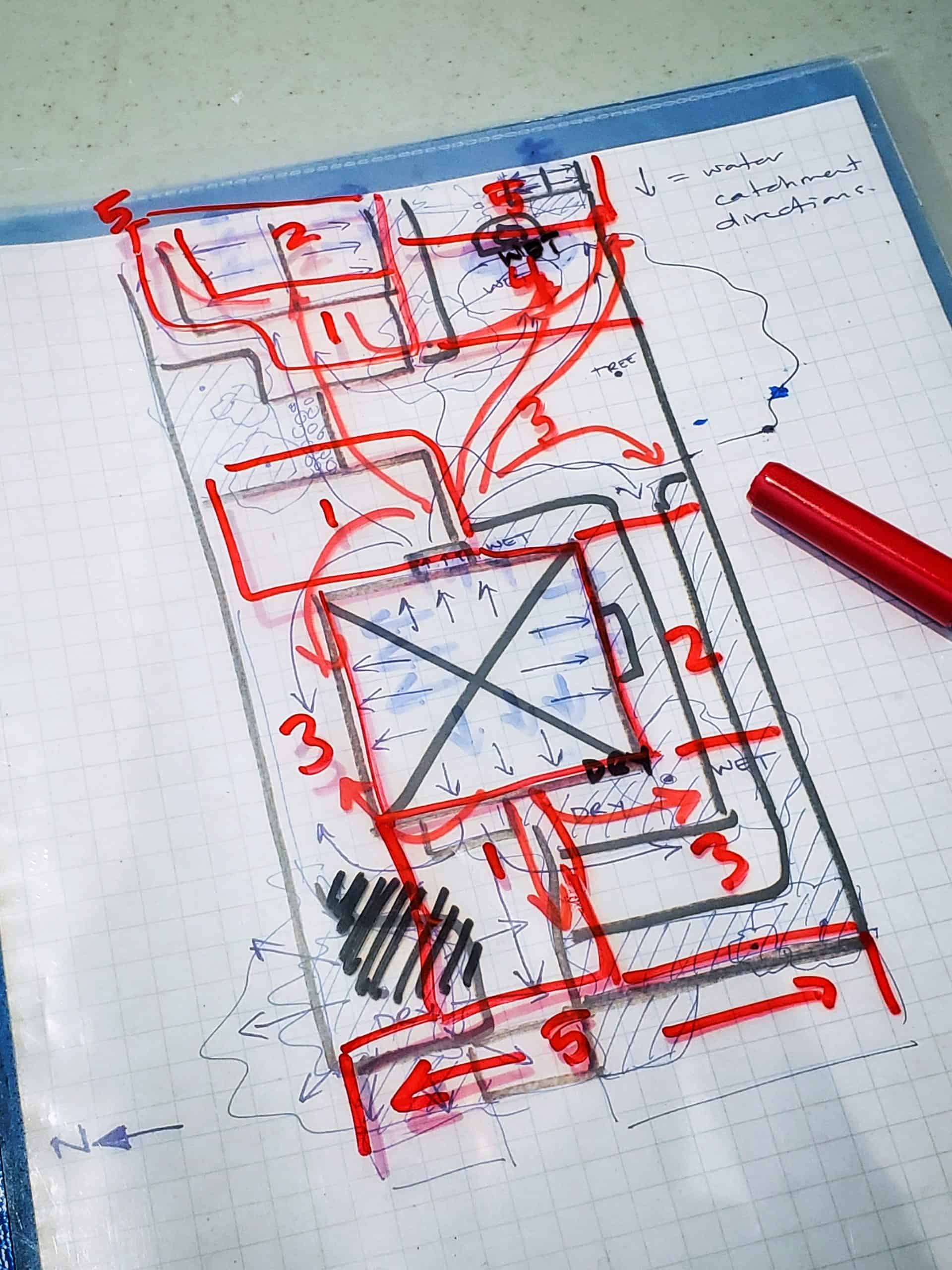

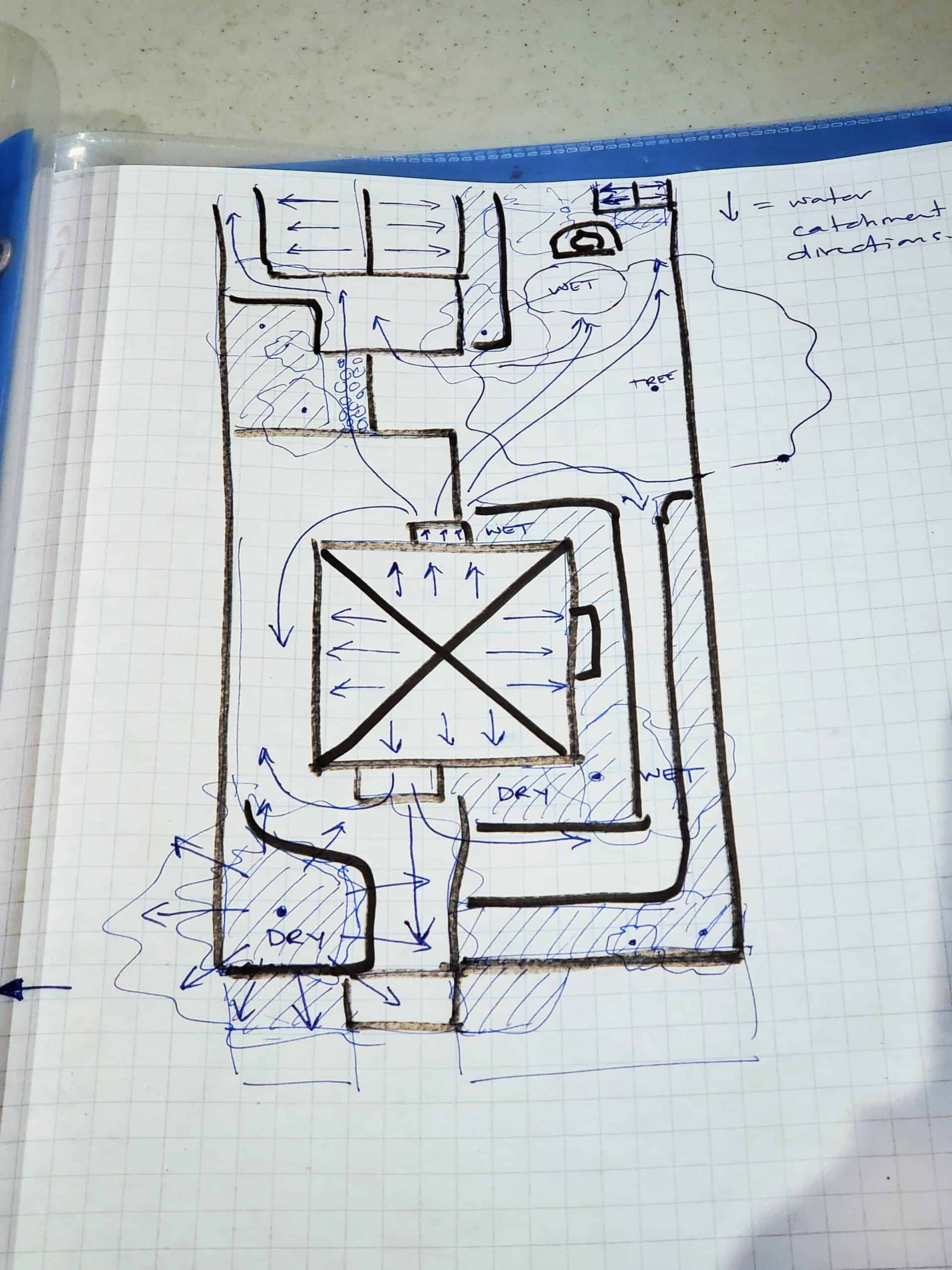

Workshop participants used graph paper, page protectors or a folder with a clear cover, a pen or pencil, and dry erase markers to sketch out their gardens. Then, they outlined their gardens on graph paper, getting permanent items down first.

Bajer explained permaculture is based on forest ecosystems. In forests, water is absorbed, transformed, and conserved. Forests take a long time to dry out, yet veggie gardens dry quickly—what can we learn?

Networks create resilience

In cities, Bajer observed, our nearest connection to nature is gardens. A Muir web, named after ecologist John Muir, illustrates that connections between living things make ecosystems resilient. More connections means more resilience; diversity creates more potential for connections.

Water, access, structures

Bajer had participants lay the clear cover over their sketches, asking, “Where does water gather?” Arrows indicate water flow from roofs, downspouts, and trees. Wet and dry spots are outlined. He shared a Verge Permaculture adage: plant your water before you plant your garden.

“How do we move through the space?” he asked, and participants marked routes with more arrows: doors to gates, building to building, and so on. These “desire lines” showed direct or meandering paths we need and want.

This included checking buildings, sidewalks, utilities, property lines, fences, and large trees and bushes. Participants added a compass, citing sun exposure. Bajer recommended everyone review their sketches at home, or make a printout from Google Earth, adding, “The foundations of design are difficult to change, so let’s work with them.”

Sectors and zones planning

Sectors are “energy forces flowing through landscapes,” said Bajer, and we can spot patterns and “increase or decrease these flows.” They include wind, sun, sound, wildlife, traffic, and even loud neighbours. Everyone coloured in sun and shade areas. He showed his yard, with a squiggle signifying noise along a shared fence, where he is planting a screen of espalier trees.

Bajer defined yards with zones one to five, near to far, and guided participants to put things they interact with regularly close by, and things they interact with rarely far away.

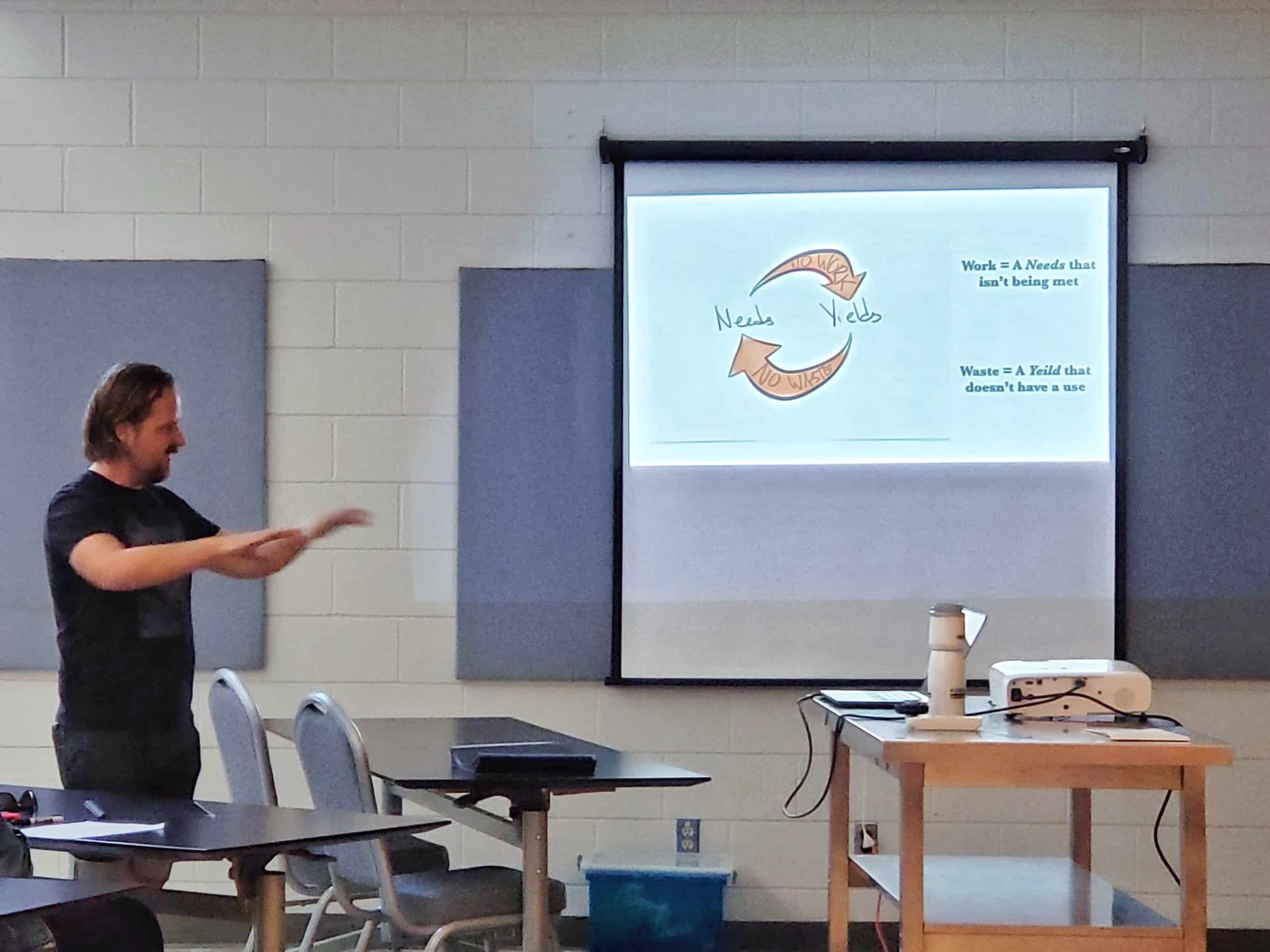

Needs and yields mapping

“What are the needs of different areas, and what does meeting those needs yield?” Bajer referenced a compost pile needing to be cool, close, not too dry, and turned regularly, and yielding living soil. A Muir web is a needs and yields web.

Bajer explained work is a need not being met, and waste is a yield without a use. A yield that fulfills a need means no waste, and a need applied to a yield means less work. He suggested doing a needs and yields analysis for five elements in a site, considering how they fit together.

The power of placement

The last exercise was to “place elements into our design based in a way that connects their needs and yields”. Bajer assured participants this is an ongoing, evolving process, and advised people to find missing connections and approach them as needs and yields.

The workshop was an engaging translation of forest wisdom to urban plots. Everyone left with budding designs and questions.